Statement of the ITUC-Asia Pacific on the World Day for Decent Work, 7 October 2021

The impacts of the global COVID-19 pandemic have been unprecedented, wrecking the world of work almost instantly when the first wave of outbreak happened in 2020. Nearly two years have passed since the first case of COVID-19 was detected and yet, the working people are still reeling from the multiple and intersecting crises that the pandemic has exacerbated.

On this year’s World Day of Decent Work, we are putting a spotlight on the decent work deficits that long existed in Asia-Pacific before the pandemic and have deepened in the past couple of years. We are amplifying our call for decent work grounded on the four pillars of employment creation, rights at work, social protection, and social dialogue. We are demanding for Just Jobs -- jobs that guarantee workers’ rights and dignity, uphold social justice, address the climate emergency, tackle the crisis of informality, and build resilience from future shocks.

The challenge of employment creation in the time of the pandemic

The pandemic gave rise to massive joblessness that pushed millions of people in Asia and the Pacific region back to poverty. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), the COVID-19 pandemic reduced nearly 8 percent of the total working hours, equivalent to a loss of 140 million jobs (based on a 48-hour working week), in the region in 2020. The job losses include 62 million people who lost their jobs entirely from retrenchment, closure of enterprises, and jobs that are maintained but at which workers spent reduced working hours. Meanwhile, 48 million unemployed people left the labour market. The crisis has disproportionately affected vulnerable groups of workers, in particular, women, youth, migrants and informal workers.

The ILO estimates that the labour market slack would persist in 2021 with 2.1-percent working hour loss, equivalent to a loss of 36 million jobs. However, this projection seems optimistic considering the new and highly infectious COVID-19 variants that spread across the region and globally throughout 2021.

Chronic social protection deficits

Asia and the Pacific has chronic deficits in social protection, which have been clearly accentuated by the pandemic. According to the ILO, more than half (56 percent) of the total population in the region were not covered by any form of social protection. Majority of whom are from South Asia, where 77.2 percent of the population were left without any social protection benefit. Meanwhile, 74.7 percent of vulnerable persons in Asia and the Pacific region were excluded from receiving social assistance. Without comprehensive and adequate social protection, workers in the region, especially the vulnerable, were not primed to weather the impacts of the economic crisis triggered by the pandemic.

The global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008-2009 highlighted the importance and urgency of guaranteeing universal social protection. Yet, despite the lesson from the GFC and the affordability of universal social protection floors according to many studies, measures to ensure social protection for all continue to be deficient and investments in social protection remain limited. In particular, only 7.5 percent of the GDP was spent on social protection in Asia and the Pacific, way below the world average of 12.9 percent. In South Asia where less than a quarter of the population were covered by social protection, the public social protection expenditure is a paltry 2.1 per cent of the GDP.

Meanwhile, the domestic general government health expenditure in Asia and the Pacific prior to the pandemic was only 4 percent (1.4 percent in South Asia) compared to the world average of 5.8 percent. With minimal investments in healthcare, the collapse of public health systems in the region during the pandemic did not come as a surprise.

Erosion of rights at work

The pandemic did not only breed joblessness; it also made the working conditions of the employed more precarious. Due to pandemic-related restrictions and uncertainties, workers faced increased job insecurity, reduced wages, declining mental health, and greater occupational safety and health risks. Even before the pandemic, almost 2 million people in the region die from work-related causes every year. Such number is likely to be significantly higher in the past year with the COVID-19 posing an additional risk to workers’ health, especially among those in the frontlines.

Furthermore, since the onset of the pandemic, we have witnessed exhaustive legislative reforms that are masked as COVID-19 responses, but effectively eroded previously won labour and human rights. Neoliberal labour law amendments in India and Indonesia have dismantled the protection of workers’ fundamental rights and promoted labour flexibilisation. Legislations that are cloaked as measures to protect national security have led to the crackdown of trade unions, civil society organisations, and activists. In Hong Kong specifically, the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions, along with other organisations, decided to disband themselves in the face of increasing threats and intimidation by the government.

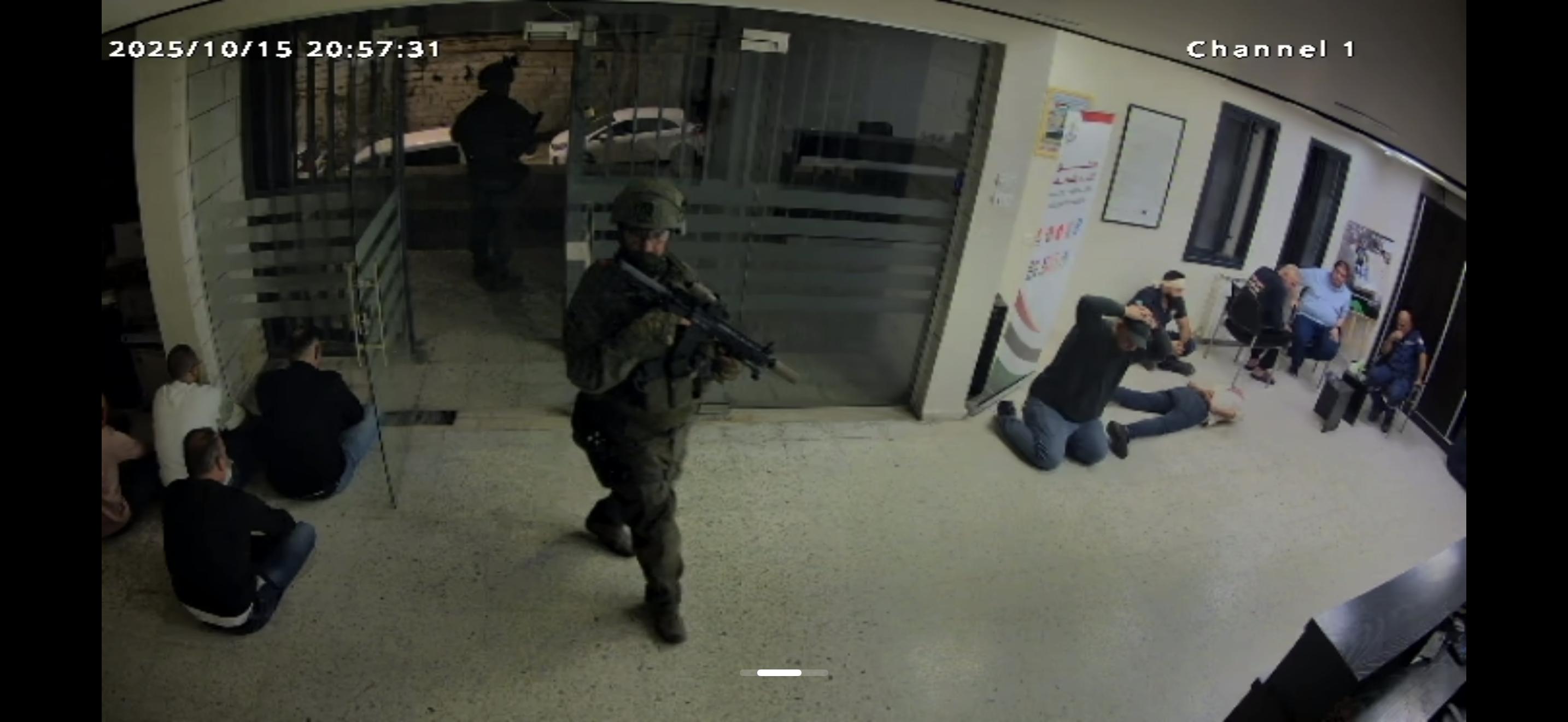

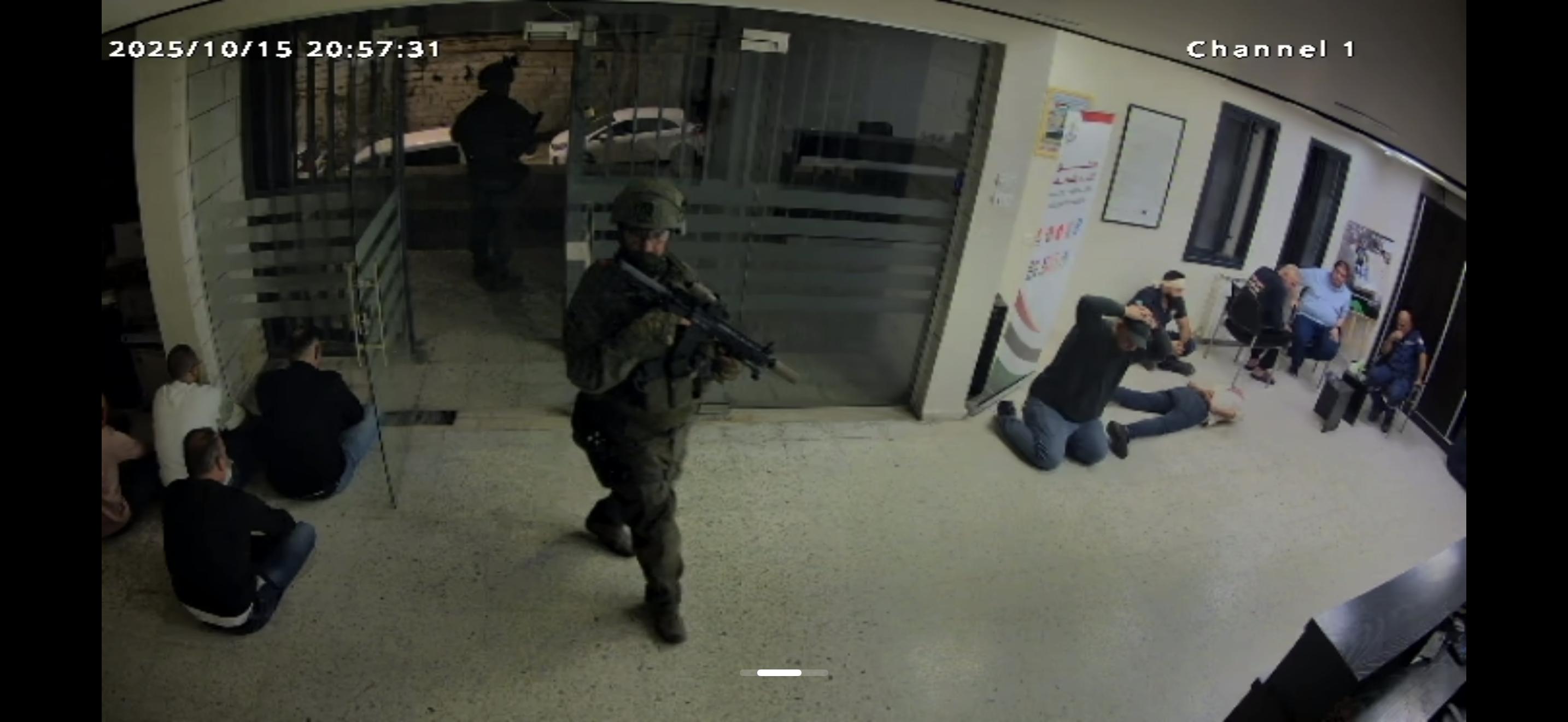

Attacks on civil and political rights also worsened during the pandemic. Workers and their representatives in Cambodia and the Philippines remain particularly vulnerable to violent attacks, intimidation, arbitrary arrests and extrajudicial killings. In Myanmar, frontline health care workers are being arrested and detained by the military junta for exercising their rights to gather and peacefully protest.

Weak social dialogue in shrinking democratic spaces

While considered an important pillar of decent work, social dialogue remains weak in Asia and the Pacific region and the regressive policies imposed during the pandemic further diminished opportunities and spaces for meaningful social dialogue among the social partners.

We highlight that social dialogue can only flourish in a well-functioning democracy that upholds the fundamental rights and freedoms of workers. Yet, out of the 39 ILO member-states in Asia and the Pacific, only 19 have ratified the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, No. 98, while only 23 have ratified the Freedom of Association and Right to Organise Convention, No. 87 and the Tripartite Consultation Convention, No. 144.

Note that the ratification of these key conventions has not led to the full implementation of genuine and constructive social dialogue. Even though social dialogue proves to be effective in developing balanced and inclusive responses in times of crisis, tripartite consultative mechanisms were not fully utilised during the pandemic. In fact, despite the existence of social dialogue mechanisms, most trade unions in the region were marginalised in formulating policies that directly affected the workers.

To illustrate, from February 2020 to 31 January 2021, there were 381 social dialogue outcomes made in 102 countries and territories. Among them, only 38 outcomes, 9.9 percent, came from Asia and the Pacific, with only five outcomes that promote long-term recovery and resilience.

Just Jobs for an inclusive, resilient, and sustainable recovery

The pandemic exposed the deep inequalities within and among countries, not only in terms of impacts but also in terms of the uneven road to recovery. While developed countries got a head start at the journey to recovery with their already existing industrial policies and immediate access to vaccines, developing countries are still suffering from the impacts of the crisis. A broader, more coherent recovery plan that addresses not only impacts of the pandemic but also the deep-seated flaws of the development framework in many Asian and Pacific countries is crucial if we want to achieve an inclusive, resilient, and sustainable post-COVID economy and society.

On the World Day of Decent Work, we put forward our Just Jobs agenda that puts the workers and the people at the centre of recovery plans.

Given the glaring magnitude of the pandemic’s impacts on employment, job creation and realisation of Sustainable Development Goal 8 on decent work and employment growth must be at the centre of recovery plans; however, it does not simply mean going back to the pre-crisis employment figures, considering the huge decent work deficits that existed before the pandemic. Recovery plans must be centred on the creation of climate-friendly jobs with Just Transition and employment in critical areas, such as care, education, and sustainable infrastructure. Also, as more than half of the 2 billion informal workers of the world are in Asia and the Pacific, countries in the region must urgently adopt measures that promote the formalisation of the workers in the informal economy in accordance with the ILO Recommendation 204.

Active labour market policies (ALMP), such as training, reskilling, and upskilling, are crucial to job creation and economic reconstruction. However, such policies have not been fully utilised across the region, including Japan and Korea. In fact, the average expenditures for ALMP in the region is only 0.1 percent of the GDP. It is high time for governments in Asia and the Pacific to put primacy on ALMPs in the job and recovery plans.

Additionally, governments must also recognise occupational health and safety as a fundamental right at work. This is more urgent and crucial than ever in the context of post-COVID recovery.

At the same time, we call on employers and businesses to fulfill their responsibility to respect labour and human rights throughout their supply chains. They must carry out due diligence to avoid and address human rights violations in their global supply chains.

Meanwhile, the ILO must continue to strengthen the capacity of its tripartite constituents and promote the development of strong and representative social partner organisations. In particular, it has a crucial role to play in facilitating the tripartite constituents’ engagement in all relevant processes, including those related to labour market institutions, programmes and policies within and beyond their borders. The ILO must also work closely with the social partners addressing all fundamental principles and rights at work, at all levels, as appropriate, through strengthened, influential and inclusive mechanisms of social dialogue. On the other hand, the UN resident coordinator has a role to play in forging the strategic partnership among diverse entities at the national and sub-regional levels, including trade unions and employers’ organisations, to advance the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and to push for the acceleration of the Sustainable Development Goals.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

%20(1).png)

%20(1).png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)